Is this from the Future?

Part 2: …Where Insights Hide in Plain Sight

The Pattern Breakers book is now available wherever you buy your books.

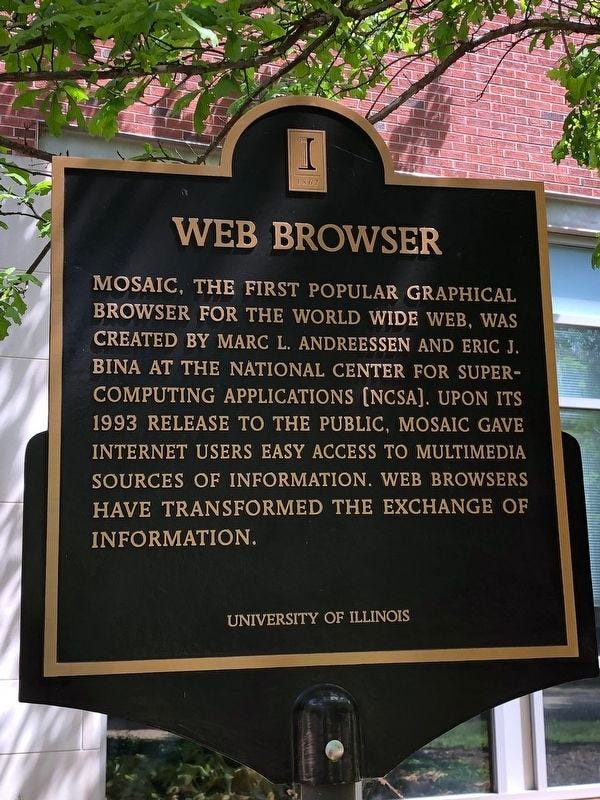

Marc Andreessen was a student at the University of Illinois in 1992. He was making minimum wage as a programmer at the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA), which was generously funded by the US government and teeming with advanced computing and networking technologies.

More broadly, several big inflections were coming together. In 1991 the government decided to allow commercial activity on the Internet. Tim Berners-Lee introduced innovations that would fundamentally define the World Wide Web, such as the Uniform Resource Locator (URL), HyperText Transfer Protocol (HTTP), and HyperText Markup Language (HTML).

Andreessen, Eric Bina, and their colleagues kept tinkering with all of these new things, exploring realms seen by very few people at that time. They noticed firsthand that the software that could make the web useful was sorely lacking. Marc and Eric decided to build what was missing and began their work on a user-friendly web browser.

The big institutions of the day could be forgiven for not noticing at first. They were engaged in a different debate about who would build the “digital superhighway.” Would it be telecoms with their extensive networks, tech giants like Microsoft and AOL aiming to dominate content distribution, or the government, who had built the real-world highways? Most expected the digital superhighway to be a top-down effort.

Few imagined the alternative: a bottom-up approach, born in a different future.

Marc and Eric, perhaps without fully knowing it, had a crucial advantage that led to fundamental insights. From their different vantage point, they saw the internet not as a digital superhighway, with its rigid structure and control by major companies, but as a dynamic, complex web that was constantly growing and changing in unpredictable ways. This understanding drove them to a design that embodied radically different first principles. They weren’t contrarian in the sense that they disagreed with the conventional wisdom. They were solving the problems they were independently interested in. Their different perspective led to Mosaic, the first user-friendly internet browser to cross into the mainstream. It would start a revolution.

People in the Future Live Differently

The Mosaic story offers a crucial lesson about founders who uncover a breakthrough insight: they are almost always living in the future, immersed in the process of cultivating new patterns of thinking, feeling, and acting through ongoing interaction with new, empowering technologies and with other people who are also living in the future.

This contrasts with the common notion that groundbreaking ideas come from being a “visionary”—as if someone sees farther over the horizon than others through a better pair of binoculars. Or they are struck by a moment of inspiration like Isaac Newton getting hit on the head by a falling apple. In reality, breakthrough insights usually come from living in the future and tinkering directly with what’s new about it—not by having opinions about it from a distant vantage point.

Why is this?

The main obstacle to creating a breakthrough startup is overcoming the limitations imposed by the established patterns of thinking shared by people living in the present. These prevailing thought patterns often blind people, including aspiring founders, from recognizing the potential for inflections to enable transformative change.

By actively engaging with the latest technologies and connecting with others who share a similar perspective, you start to develop new ways of thinking and acting that differ from the norm. This helps you escape the limitations of the present and envision alternative futures. The world as we see it and the assumptions that shape it—the world that is—is just one of many ways to envision the world that could be.

Build What’s Missing in the Future

There’s a certain magic in crafting something with your own hands, to solve your own problem, that you experience in the future.

The Mosaic team wasn’t focused on a “market for browsers” when they set out to build it; they were solving a problem that they were experiencing in the future firsthand. They were interacting with new types of computers and networks every day. They were discovering new things and facing challenges that most people didn't even know existed yet. They were solving important problems of the future before others were even aware they existed.

The example of Mosaic’s success leads me to one of my all-time favorite Paul Graham essays, written for aspiring founders seeking great startup ideas:

I've been a dedicated follower of Paul's writing since Hackers and Painters, which he authored before I was an investor and before the founding of Y Combinator. Even among his consistently excellent works, this essay stands out to me as one of his finest.

Paradoxically, he advises against “trying to think of a startup idea” because he believes that the best ideas don't come from attempting to force innovation this way, which is too synthetic. Instead, the most successful startup ideas often emerge organically from the founders' personal experiences, particularly from their attempts to solve real problems they encounter when they dive into cutting edge technologies they experience by living in the future. He argues that this approach ensures a deeper understanding of the problem, making the solution more likely to be effective and valuable.

There are Many Ways to Live in the Future

You don't have to work in a high-tech supercomputer lab with advanced tools available to only a select few to discover future needs and opportunities worth addressing.

You can also identify future needs that affect others, not just those you experience personally.

Todd McKinnon and Frederic Kerrest, co-founders of Okta, provide a good example. They were early executives at Salesforce, and their experience interacting with customers at the forefront of the cloud-computing revolution gave them a unique glimpse into early adopters' challenges.

Unlike Mosaic, where the founders solved their own problems, Todd and Freddy leveraged their intimate understanding of problems encountered by early adopter customers of cloud computing. They recognized a widespread problem among them: the need for unified access to multiple cloud applications without separate logins for each. This insight led to the creation of Okta, a solution providing seamless access to all cloud apps with a single login.

Okta's origin story highlights another way to live in the future: by identifying and solving the problems of customers who are ahead of their time and who you know better than others, even if their problem isn't personally yours.

But what if you are not living in the future, either when it relates to your own problems or problems experienced by the innovative customers you know best?

Maddie Hall, the CEO and cofounder of Living Carbon, provides an example of proactively seeking out different futures.

Maddie was a product manager at Zenefits, a cloud-based human resources platform. She decided she wanted to start a new company and initially went about it by trying to think of start-up ideas. But then she decided to work on special projects with OpenAI CEO Sam Altman instead. Maddie’s tour of duty with Sam offered her another way to get unique glimpses into the future.

Over time, Maddie was immersed in the development of cutting-edge models like GPT-3 and DALL·E and observed timely discussions on AI ethics and policy across various sectors.

A meeting at Microsoft underscored the company's dedication to significantly reducing carbon emissions and guided her towards exploring plant biotechnology as a means to assist companies like Microsoft in reaching their environmental goals.

As she studied the topic in more depth, Maddie saw that recent research made it possible to introduce technology to genetically modify trees to grow faster and take more carbon from the atmosphere.

This interest led her to partner with botanist Patrick Mellor in co-founding Living Carbon. This is a far different way of finding an insight than the approach she initially considered of brainstorming for startup ideas when she was thinking about life after Zenefits.

More than a play on words

To some, the idea of "living in the future" instead of the present might just sound like playing with words. Isn’t the very act of creating any start-up an effort to live in the future, by definition? Aren’t all start-up founders envisioning a different tomorrow?

I understand why some people might think this way. However, there's a crucial detail that's easy to overlook.

Many founders are choosing where to focus their creative energies without even realizing they're making such a choice. The critical decision to be aware of is this:

When founders build for a future that’s an extension of the patterns of today, they create a future that’s an improved version of the present. This is enticing because the route to success is more straightforward and recognizable. Others may be less likely to push back on your ideas. But in this clarity and comfort lies a trap, because following existing rules inherently constrains your potential to achieve outsized impact.

The pattern breaker seeks to build for a future that will break sharply from what we know today. They focus on discovering inflections and insights that enable them to deliver a pattern-breaking solution. This path is not for everyone; you’re piecing together a path forward without a clear map. However, it’s precisely this absence of preset landmarks and limits that offers enormous potential. You’re not confined by the boundaries established by others; instead, you have the freedom to create new boundaries.

In the earlier example of the commercial Internet, people who thought the future would be an extension of the present believed that the digital superhighway would be built and defined by the old guard—the phone and cable companies, the tech giants, or the state.

The Mosaic team, by contrast, started from a very different idea of what the future would look like, making use of the newly released protocols of the World Wide Web. The Mosaic team decided what to build by directly observing the obstacles they faced while trying to unlock the full potential of the new capabilities. They were getting feedback from like-minded early internet users, who were also living in the future and exploring this uncharted territory. The team created a solution that was radically different from the walled gardens or top-down networks favored by those who thought the future would extend from the patterns of the present.

William Gibson was right

The cyberpunk author William Gibson says it perfectly:

His words offer founders a key lesson: the future holds insights for the few who spend time there first and pursue their curiosities authentically.

Traditional approaches to thinking of startup ideas often trap entrepreneurs within existing thought patterns, limiting their ability to see and exploit transformative opportunities.

To find the best insights, it's better instead to look for opportunities to live in the future. It’s more effective to immerse yourself in cutting-edge technologies and understanding how to unlock their potential for creating radically different futures. This process enables entrepreneurs to intuitively identify missing elements that can more likely lead to non-consensus insights that lead to huge breakthroughs.

There are lots of ways to get out of the present. You can tinker with cutting-edge technologies and solve your own problems like the Mosaic team. You can solve them for customers that you spend time with who are living in the future like the co-founders of Okta. Or, like Maddie Hall at Living Carbon, you can catapult yourself into different futures.

But ultimately, the best cheat code I’ve seen for discovering insights remains the same:

Get out of the present.

Exceptional pattern breaker read for this creative entrepreneur that lives in the future. Love the insights you included from Paul Graham too. I like the idea of, "what do people really want you to solve for them". What do the big players who believe, "the future will extend from patterns in the present" and might be missing. I love the insight, "the place to start looking for ideas are the things you need".-