Reality Doesn’t Negotiate

Seek reality, not validation.

In January 2020, at CES in Las Vegas, Jeffrey Katzenberg took center stage. He was there to pitch Quibi, his bold $1.75 billion bet that aimed to revolutionize mobile entertainment with ten-minute video ‘quick bites.’ But, he could feel a palpable sense of skepticism from the audience of tech reporters and twenty-somethings.

He stopped mid-pitch and said something that only makes sense if you’re certain you’re right about how the world works.

“I’ve been doing this before you all were fucking born.”

He had the résumé to back it up. As head of Walt Disney Studios, he had greenlighted The Little Mermaid and The Lion King. He had co-founded DreamWorks with David Geffen and Steven Spielberg. He had seen the future of entertainment several times, and each time, the future had bent to his will.

Four months later, Quibi launched.

Eight months after that, it no longer existed.

Despite Katzenberg’s validated instincts in entertainment, the failure of Quibi highlighted a crucial truth: reality is indifferent to past achievements. His track record was built on respecting reality’s terms, not his own.

One No Beats One Hundred Yeses

The difference between successful founders and those who fail often hinges on a critical factor: their relationship with being wrong.

Some founders treat their thesis as a hypothesis to be tested. Others treat it as a conclusion to be defended. The first group seeks reality. The second seeks validation. And the second group often finds elaborate and expensive ways to confirm their beliefs.

Why does hunting for criticism beat seeking validation? Because criticism is asymmetric. One disconfirming fact can eliminate an entire category of error. A hundred confirming facts can’t prove you’re right; they can only fail to prove you wrong. The philosopher Karl Popper called this falsification. Theories can never be proven true; they can only be proven false. A thousand white swans don’t prove all swans are white. One black swan ends that debate.

In founder terms, a test that cannot plausibly compel you to change course is not a genuine test. The real mistake isn’t being wrong; it’s creating systems that hide mistakes, stopping us from learning and adapting.

Once you see it, the logic of validation collapses. You’re already embedded in a process of conjecture and criticism whether you like it or not. Every day, the market criticizes your theory. Customers who don’t return criticize your theory. Features that don’t get used are criticisms. The question isn’t whether to invite criticism into your process, but whether you’ll engage honestly with the criticism that’s already happening.

Why Airbnb Wasn’t A Guess

Brian Chesky and Joe Gebbia put up a WordPress site out of desperation, not foresight. They couldn’t afford rent and needed quick cash. So they offered strangers a place to sleep on an airbed in their apartment. A surprising number of strangers were eager to say yes.

Most people would have written off those guests as outliers. Chesky asked a different question: does this reveal something important that everyone’s missing?

The behavior of strangers trusting strangers was surprising, but it was also real. Chesky didn’t have to imagine it. He’d seen it. His job was to understand it and amplify it. Once he reframed the behavior as a clue rather than a fluke, he could test a conjecture: if strangers can trust each other, hospitality can be reinvented. Professional photos increased bookings. Reviews drove repeat stays. Better payments reduced friction. Each experiment sharpened the picture.

They found product-market fit because they kept accepting reality’s terms.

However, Airbnb’s relationship to criticism is complicated; Chesky also ignored much of it. Investors called the idea insane. The early data looked terrible. If he’d been purely responding to criticism, he might have quit.

What he actually had was a specific form of stubbornness. He trusted the behavior of the guests who showed up, even when every other signal said stop. That’s not ignoring criticism. That’s knowing which criticism to trust.

Guests who stayed shared real experiences, while investors who didn’t join in just talked about market trends. They didn’t really know if the behavior was genuine. The real mistake is not telling apart valid criticism from just opinions. Chesky could tell the difference.

And there’s a deeper layer: the surprising behavior had an explanation. Both sides of the market were desperate. Hosts needed the money badly enough to let strangers into their homes. Guests couldn’t afford hotels. Desperation on both sides made “strangers trusting strangers” possible and replicable. Chesky noticed the behavior and desperation explained why it could scale.

Earned Conviction

Chesky trusted behavior over opinion, and he was right. But for every founder who ignored critics and won, ten thousand ignored critics and lost. What separates them?

The difference is between earned conviction and performed conviction.

Performed conviction is a man on stage telling twenty-somethings he’s been doing this before they were born. Earned conviction is a stranger handing you cash to sleep on your floor.

The success rate for ‘I believe something others find absurd’ is dismally low, often because such ideas are dismissed for valid reasons. What made Airbnb work wasn’t just courage or contrarian thinking. It was evidence. Chesky and Gebbia had actually hosted people. They’d seen it work. The conviction came from contact with reality, not just their reasoning about reality.

“Be contrarian” is dangerous advice when it’s just a bumper sticker. Performed conviction feels like earned conviction from the inside. The founder feels certain, but the certainty isn’t attached to anything real.

This is why smart people are particularly vulnerable. Intelligence becomes a liability when it helps you explain away a failed test. If a customer doesn’t return, a disciplined founder asks why. A clever founder invents a reason it doesn’t count.

Falsification doesn’t just cost time or money; it can cost you your identity.

For most founders, the challenge isn’t spotting great ideas; it’s avoiding the pursuit of bad ones. Venture returns follow a power law, but that cuts both ways. A founder cannot get five years of their time back on a company that was never going to work.

If you’re living in the future and have a prepared mind, you’re more likely to recognize the great idea when it arrives. What you need is the discipline to not fool yourself while you wait.

Falsifying Your Way to Product-Market Fit

You don’t validate your way to product-market fit. You falsify your way there.

The theory that survives every serious attempt to kill it is the one worth betting on.

This means testing three conjectures by exposing them to criticism, not confirmation.

The What: Is the Problem Real?

The wrong question: “Is this a problem for you?” The right one: “Have you already tried to solve this? What did you spend—time or money?”

The Who: Can This Person Act?

“Does this resonate?” tells you nothing. “If this solved the problem, could you buy it this quarter? What would stop you?” tells you everything.

The How: Can the Business Model Work?

Rather than “Does this pricing feel reasonable?” Go straight to having the willingness to pay conversation as early as possible.

The Trap of the Brilliant Excuse

There’s a failure mode just as dangerous as avoiding criticism: you run a test, the result comes back negative, and instead of accepting it, you explain it away.

Those weren’t our real users. The metric doesn’t capture what matters. We just need more time.

This feels like critical thinking. Actually, it’s the other way around. You’re trying to fix a claim after it’s been proven wrong to avoid admitting it.

The possibility that you’re wrong doesn’t disappear because you avoid the signal. It compounds.

You can pay now, in small installments, as you discover what’s broken and fix it. Or you can pay later, in one catastrophic sum, when reality delivers the verdict you refused to seek.

That’s why so many failures feel sudden. They aren’t. They’re the interest on deferred falsification, coming due all at once.

On Reality and Its Rewards

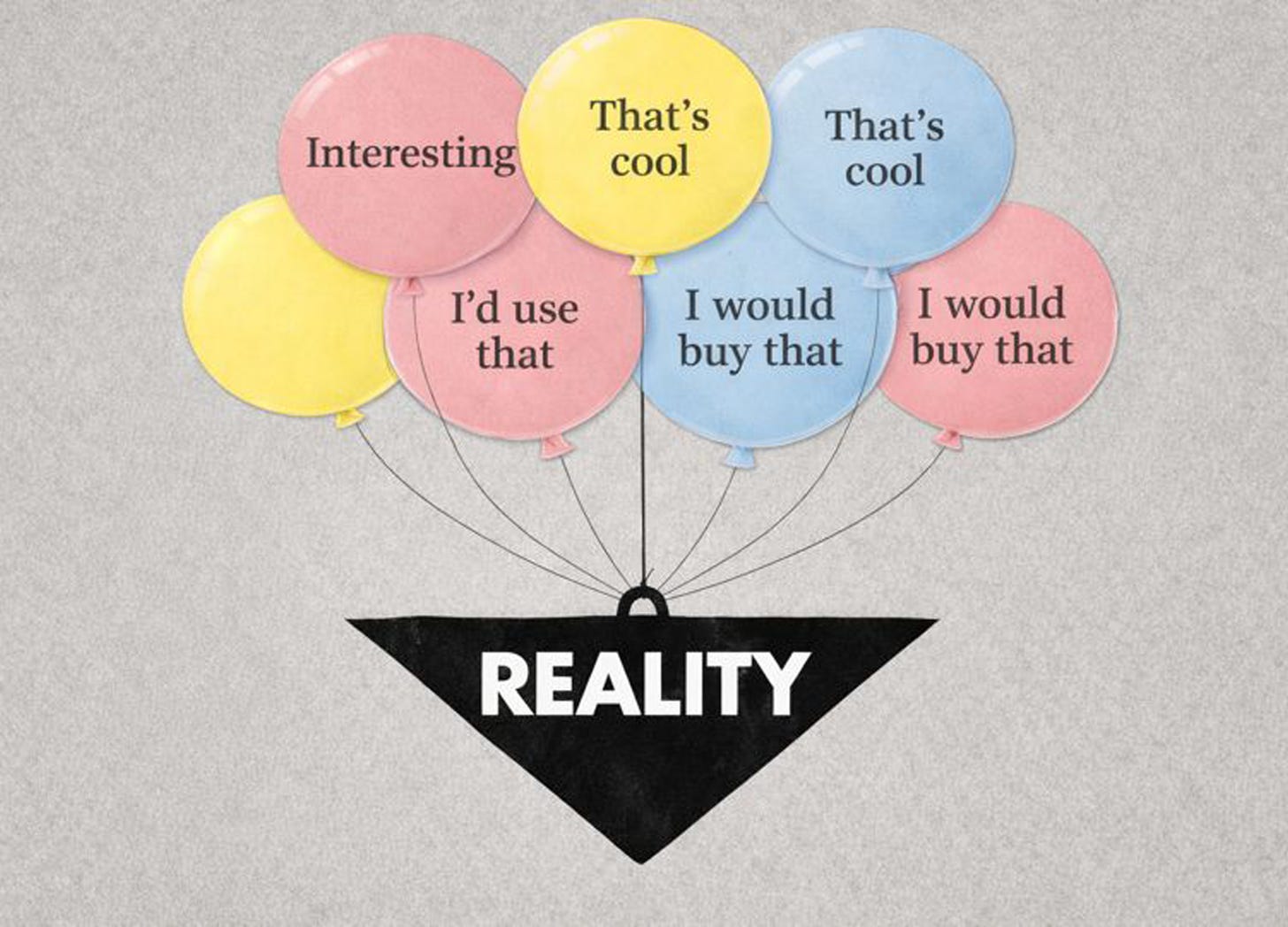

There is a truth waiting for you. It might be sitting in the churn report you skimmed but didn’t study. It might hide in the pause after someone said “interesting.” It might live in your gut, in that feeling you ignore because you’re not ready to hear it.

You need to go find it.

Falsification isn’t the enemy of conviction; it earns conviction. Every hard truth you face today is a reckoning you don’t face tomorrow. It’s not an obstacle. It’s the path.

You have a choice in how reality finds you. You can wait for it to arrive suddenly and expensively. Or you can go looking for it now, while it’s still cheap to be wrong. You can design tests that expose your ideas to genuine criticism. You can learn which signals actually matter and which are just noise shaped like validation. You can earn your beliefs instead of performing them.

Reality doesn’t negotiate. It doesn’t care about your timeline or your burn rate or how much you’ve already invested.

But it makes better deals with those who listen.

Loved this, and so guilty of much of the behaviour that feels smart but really isn't, falling into the trap of brilliant excuses.

It makes me realise how load bearing the word "truth" is in Peter Thiel's famous question - "What important truth do very few people agree with you on?”. It's easy to focus on the importance (impact) or "few people" (contrarian) view of your ideas and completely miss the reality.

excellent article!